Well, these two jobs have occupied most of October. Before I really got into them, however, I finished fitting the hoop.

Gluing it in place was a fiddly business. Ideally, I would have attached it to the frame 50 mm abaft where it ended up, which, indeed, was my initial intention, but it interfered with the wind vane. I could have made a new windvane. I decided it was easier to move the hoop further forward.

And here it is in place, awaiting paint. It's fairly sturdy, as long as no heavy person decides to swing from it. One can't legislate for every eventuality.

I bought the Oregon for the mast when I started building the boat. (In NZ, Oregon is used to discriminate the high-quality, imported wood from the locally-grown, Douglas fir.) It's beautiful wood, very fine grained and straight. David had suggested I build a hexagonal mast. In retrospect, I wish I had bought 8 boards: it would have been easier.

When making a birdsmouth mast with six sides, the angles need to be 30° and 60°. I puzzled over this for some time before deciding the easiest thing would be to cut up some pallet wood and make a mock-up from this. That would allow me to work out how to do the second cut.

I couldn't get the table saw blade to go down, so in desperation I went to Master Boatbuilder, Noel Barrot, and asked him for some advice. He very kindly spent the best part of a morning, dismantling the table and splashing oil around with joyous abandon after I had removed the grunge of decades from various orifices. The blade moved up and down with wonderful ease and precision after this. I then cut the first angle on the pallet wood and discovered that by turning it on edge, I could then make the second cut of 30°. It was gratifyingly straightforward.

All the information I needed to work out angles, thickness, strength (a bit of a closed book to me, I have to confess), etc I gleaned from the Duckworks site: Birds Mouth Spars revisited. This also gave me the dimensions for the tapered top of the spar, which was different from what I had assumed, which saved me from a real blunder. I discovered this site from Gary Pick's excellent article in JRA Magazine no 57. Gary also very kindly answered several emails from me while I was groping my way forward.

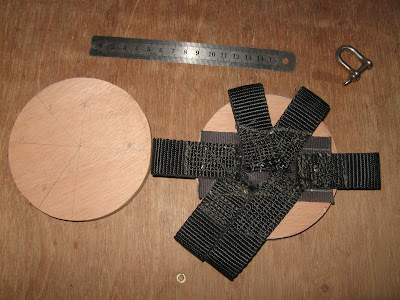

Having cut up the pallet wood, I cut it into 6 pieces and roughly put them together to see how this concept works.

With my heart in my mouth I prepared myself for the Real Thing. Fortunately for me, Gordon was passing on his way to Auckland and, yet again, allowed himself to be shanghaied into not only getting the 6 m tube down and onto a bench alongside the shed, but helping me machine the Oregon. Another reason I was glad that he was there was that the pieces of wood, well over 4 m long, wouldn't fit through the gap in the stairs, when they were on edge. This meant the removal of one of the stairs, which Marcus had secured with every intention that it should stay in place. Wielding a hammer to good effect, Gordon not only managed to remove it, but also to replace it once the job was done. I had paid about $1,000 for this wood, so it was, to say the least, nerve-racking, sending it through the saw.

However, it all went without a hitch and I soon had a stack of nicely-milled timber awaiting the next move.

Here you can clearly see the birdsmouth. You can also see why the 45° would be easier to work with than the 30° and 60°. The smaller joint is a bit more fragile than ideal.

Gordon carried on his merry way, and I cleaned up all the grooves. Noel suggested knocking the back off the part that would adjoin the groove, as well, to ensure a better fit and plenty of glue.

The next stage was to taper the staves. Ideally, I would have started the taper from 600 mm up, so that the base would have been straight and easy to put into the alloy tube. However, I didn't see how this could be glued together so with the aid of the invaluable website, worked out what the base should be and marked out a straight taper from top to bottom. My little battery-powered circular saw did the work. I cut the 35 mm staves in three stages of increasing depths, but the poor little saw still struggled and it had to have a rest at the halfway point for its battery to be recharged. As I was still finding the whole business quite stressful, terrified that I would make some irremediable mistake, these enforced breaks were good for me, too.

The next job was to glue up the staves. I didn't want to do it in one hit, because I wanted to put a wire up for the masthead light and I also wanted to be able to check that (at least half!) the joints had glued together properly. At first, I planned to do it in two stages and then glue the two halves together, but then I thought that only a little distortion could make this very difficult, so decided to do it in just two stages.

The first 2 pieces could be temporarily clamped while I prepared the third.

Holding the three pieces secure was something of a challenge, and this is one of the cases where an 8-sided mast would have been a lot easier. Clamps simply wouldn't work and, if anything, tended to distort the shape, however carefully wedged. I had discovered this as soon as I had tried a dry fit, so in the end decided to use cable ties. I couldn't exert that much pressure - or I ended up back at the clamp situation. This is one of the situations where epoxy is superior to most other glues: it doesn't require any clamping pressure to speak of. Anyway, it all went together fine.

Once the epoxy had set, I tried a 'dry run' to check that everything went together well and it did. The third piece slid in easily and fitted acceptably. However, the act of sliding it would tend to remove some glue, so I would have to be generous.

I coated the inside of the three pieces that were to be fitted next.

I also coated the inside of the already-glued mast and laid the wire for the tricolour light along it. With wire being relatively stiff, you might think it would be easy to slide it in after the event. However, as I have learnt the hard way, it isn't and with the very real chance of lots of glue drips at the next stage, I reckoned that there would probably be too many snags to make it easy to send a mouse down, too.

Again, I assembled it all with lavish amounts of glue, but as so often happens, in spite of there being a very good fit the first time, when it came to the final job, the 'shutter plank' was a struggle to get right. Don't ask me why. In fact the very bottom of the mast ended up a far from perfect hexagon and there were gaps along a couple of the glue joints. However, there was nothing that could be done about it, so I just secured it all together as well as I could and hoped I'd be able to sort it all out after the event.

Noel, kindly mentoring this whole business, told me that the next task was to turn the six sides into twelve. Google was no help at all here: the only reference I could find to a six-sided mast was due to the fact that the fellow writing it didn't know a hexagon from an octagon. With eight sides, you can use Pythagoras to work it all out, with six you have to be a little more empirical. Tony from the boat next door, lent me a chalk line and I carefully assessed the mast by eye (not at all my strong point) and marked where I should plane to.

Noel had also suggested that at this stage, instead of going for a straight taper, I should go for a spar taper (which I assume is the same thing as the barrel taper, mentioned in Practical Junk Rig) Supposedly it is more pleasing to the eye, but quite honestly, I can't see the difference. Still, the Master was helping and the least I could do was follow his advice.

At the early stages, I could use a power plane, but before long I was using a hand plane. I'm afraid Noel was somewhat unimpressed at my attempts at sharpening my planes (I can't say I am surprised, it is still a skill I have to perfect) and kindly took them off with him to hone to a scary degree of sharpness that I could only envy.

The object of the exercise was pick several points along the mast, work out what diameter they should be and then keep planing, turning and measuring. The initial part of the shaping was done by taking a long plane from one end of the mast to the other, in one sweep 5 times. Then I turned it and did the same on the next face and so on. Then it was all measured and as time went by, I could take more (or less) off each face until the mast became more even.

I used a hole saw to make patterns and Noel lent me calipers to check further down the mast.

Finally, I had 12 even sides. Then came the best bit: Noel lent me one of his treasured wooden planes (found in the Falkland Is), which has a radiused base so that it takes off all the corners and produces a curve. It was a lovely thing to use.

By putting chalk on the inside of my plywood patterns, I could find the high spots and attack them individually until the whole mast was smooth and even.

The last little high bits took the longest to smooth down, but finally I decided that it was good enough.

Of course, I now had a nicely tapered spar, but the base of it was far too big to fit inside the alloy tube. So the next job was to shape that.

I carefully marked it, measuring from the top of the mast and then roughly planed the lowest part to within coo-ee of the desired 142 mm. Noel's suggestion was to use a router to take off the bulk of the excess wood and then finish it off with a plane. Noel is not a man who lightly recommends the use of power tools, and I find using the router freehand a bit daunting. However, I gave it a go on the principle that if I did make a big gouge where I shouldn't, I would at least be able to fill it again.

I actually found it a bit easier than I had anticipated and the router only ran away with me once. Much planing followed, both along the mast and, at the top, across the grain, which left a bit of a mess that I cleaned up with my block plane. I had made another pattern with a 142 mm hole saw, which was invaluable for getting this section shaped.

Finally, the spar was ready to sand. Noel told me about using a long strip of snanpaper and pulling it back and forth around the masts circumference to remove the excess and again work on any high spots. It was insanely efficient. It was also an exceptionally good workout!

With the mast sanded, I could now try it for size.

To my gratified astonishment, it slid gently into the alloy tube at the first attempt.

I have to say, I did a rather better job with this one than I did on Fantail. On the other hand, I also had plenty of wood - and Noel!

As I mentioned earlier, some of the joints weren't all they could be. I had tilted the mast, top down, and run glue down the inside where one joints seemed to be more open than I was comforable with. Shining a torch down the inside, most of the joints looked OK, but there were still a few places where the glue had blown bubbles, dripped out or generally not done as it should, so I went back and filled them all. I had been concerned that maybe some of these holes were serious, but they were filled easily, so I think the mast is probably sufficiently well stuck together.

And as added insurance, I put a 'Band-aid' of glass and epoxy around it. In fact, the glass and epoxy is to make it nice and hard for the ropes that will pass around it, moving constantly when the boat is under way.

At the very start of this project, my friend, Paul, at All Marine, gave me a roll of fibreglass. Over the years, several friends have taken advantage of it for covering masts, dinghies, etc and I was hoping that I would still have enough for covering the mast. When I had finished, here was about 50mm left over. Thank you, Paul!!

I also put some fillets inside the mast up to the 'partners'. The Duckworks site reckoned that the walls were thick enough, and equally to the point, so did Noel, but those additional fillets gave me an extra sense of security.

The whole spar was coated again and is now ready for sanding and painting.

I had always hoped that there would be enough Oregon left over to make my yard. There is a school of thought that a 'fat oval' is better than the yard suggested in PJR and I debated whether to make one of these (using my newfound skills to produce a barrel taper) or to go for the classic design out of the book. As it turned out, the wood that I had was only suitable for the latter, but I am actually perfectly happy with going that route. After all, this is how we made the yards on Badger, and to the best of my knowledge and belief, they are still going strong.

I roughly shaped the boards before gluing them together and then knocked off the majority of the excess with a power planer. After the initial glue up, I was a bit concerned that I had made a mistake. The yard weighed a ton. I like a bit of weight to bring the sail down, but this was ridiculous! However, I carried on planing and shaping and in the end was delighted at how light it has turned out to be! Heavy enough to bring the sail down: light enough to hoist without too much effort. Just what I wanted.

I finished the job by hand, again surprised at how good a finish one can achieve with hand planes, so that the final sanding takes only a few minutes. I rather enjoy looking at the 'traditional' yard. It brings back many happy memories. I wonder if I will be able to resist the temptation to varnish it!

I swept up and filled a large bin bag with the shavings. There was another half bag in addition to this. Very expensive wood shavings!